The plunge in both short-term and long-term interest rates has sparked a debate about how other asset classes respond, including equities. In the article below, I outline my thoughts on the impact low interest rates can have on the equity market and factors to consider in these conditions.

Whilst a further melt up in equities is possible in the short-term as frustrated yield hungry investors readjust their portfolios, investors will need to weigh up how to manage the risks as valuations become increasingly divorced from long-term fundamentals and lower yields send conflicting messages.

We must acknowledge some basic truths:

- Equity investors are being asked to make long-term and risky investment decisions whilst policymakers’ decisions must respond to short to medium-term needs, which can change rapidly. Just months ago, the US Federal Reserve was on a determined path of tightening. Within weeks they retreated. Despite this, market participants seem remarkably eager to assign enormously higher valuations to the current market not knowing if policymakers might suddenly turn again and severely (maybe even permanently) impair the valuation of some of their equity holdings.

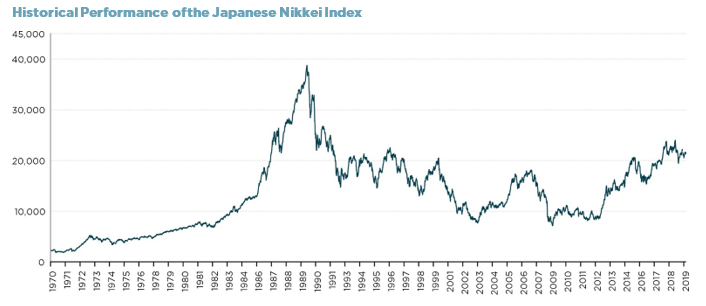

- The observed experience. Every time the “this time is different” argument around debt, deflation, demographics and long-term yields rears its head it inevitably leads to discussion of Japan, the only country that has had to face exceptionally low rates for an extended period. But if low rates are good for risk assets then why has the equity experience there been abysmal? Undoubtedly the market got well ahead of itself in 1990 and Japan has only applied quantitative easing sporadically in the intervening years. But it’s not as if permanently low bond yields in Japan have led to a “permanently high plateau” in equity price-to earnings ratios which we are being asked to believe are logical because rates are low. After all, the Japanese equity market still trades well below levels of 30 years ago as seen in the chart below.

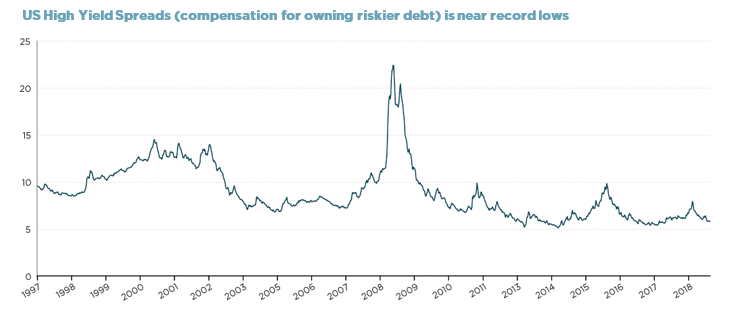

- We must acknowledge the Federal Reserve’s ability to set rates but also the market’s ability to set rates through credit spreads. The chart below shows how dramatically the cost of business debt rises during recessions, regardless of action taken by the Federal Reserve. Of course central banks could intervene here as well and purchase high yield bonds (although even they have been hesitant to apply public money to the purchase of what used be called “junk bonds”, which would surely be the last and most desperate effort in the great modern monetary experiment).

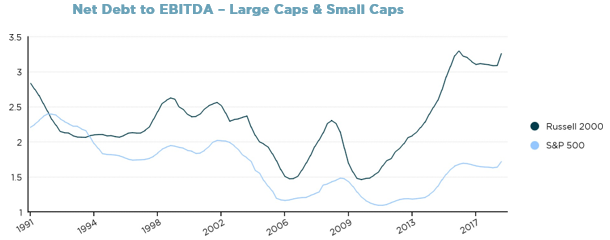

This problem will become particularly acute as the US, in particular, must confront the huge corporate debt bubble that has built up in recent years, especially in the small cap sector, where a crisis is surely brewing. The chart below shows that US corporate debt is at near record highs.

Ironically, we’ve seen this entire scenario not that long ago. The brilliant economist Arthur Laffer argued, amongst other things, that low long-term interest rates justified a rise in equities which were 67% undervalued in his opinion. The problem with the argument was that it was made in January 2007. Whilst in theory the low interest rates of the time could easily be plugged into an equity market valuation model to justify a much higher market and price to earnings ratio, the reality was that rates were low because the bond market realised a significant recession was coming. The technicals of the bond market were being used to justify something wildly different to reality; the tail was wagging the dog. That recession turned out to be the GFC and shredded the equity market in the two years from 2007-2009.

This is not to say we are predicting another GFC but whenever a large and sudden plunge in interest rates are being used to justify exceptionally higher prices for risk assets like equities, you have to ask if this really makes sense or if, once again, the tail is wagging the dog.

Disclaimer: This information has been prepared by Perpetual Investment Management Limited (PIML) ABN 18 000 866 535, AFSL 234426. PIML is the investment manager of the Perpetual Equity Investment Company Limited (Company) ACN 601 406 419. It is general information only and is not intended to provide you with financial advice or take into account your objectives, financial situation or needs. You should consider, with a financial adviser, whether the information is suitable for your circumstances. This information does not constitute an offer, invitation, solicitation or recommendation with respect to the purchase or sale of the Company’s securities. To the extent permitted by law, no liability is accepted for any loss or damage as a result of any reliance on this information. This document may contain information contributed by third parties. PIML does not warrant the accuracy or completeness of any information contributed by a third party. Any views expressed in this document are opinions of the author at the time of writing and do not constitute a recommendation to act. References to securities in this publication are for illustrative purposes only and are not recommendations and the securities may or may not be currently held by the Company. Past performance is not indicative of future performance. This information is believed to be accurate at the time of compilation and is provided in good faith. No company in the Perpetual Group (Perpetual Group means Perpetual Limited ABN 86 000 431 827 and its subsidiaries) nor the Company guarantees the performance of the Company or the return of an investor’s capital.